Shutter Speed

Shutter speed is like an onion. It appears simple on the outside, but there are actually layers of complexity associated with it.

Here's the good news: you don't need to understand all of this complexity at once.

In fact, this is part of what makes photography such an interesting hobby: there is always something new to learn. Just when you think you have a complete handle on how to use shutter speed, you read an article about some new technique that takes months of practice to perfect.

But we're not going to dive down to that level of detail in this article. Instead, this is the high-level introduction: what it is, how it works and why it's one of the three most important settings on your camera.

A Brief Moment of Light

I often compare how your camera sees the world to how your eyes see it because once you understand the differences, what you see in your photos makes a lot more sense.

As you walk down the street, you're able to see everything

clearly: people walking, joggers running, bicyclists pedaling and even cars zipping by. It's pretty easy for you to see details, even if those details are on objects passing by at high speed.

Your camera doesn't work exactly the same way. There will be times (many of them) where you see something sharp and clear that your camera captures as a massive blur.

However, once you learn how to control shutter speed you will be able to take pictures of things that you can't see with your eyes...like what happens in the instant when a drop of water hits a pool of still water.

Here are the mechanics of how it works:

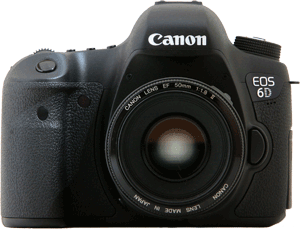

- The shutter inside your DSLR sits in front of the sensor and blocks it from light

- When you press the button to take a picture, the shutter snaps open and exposes the sensor to light for a very short time

The time that the sensor is exposed to light is called the shutter speed.

Often, these speeds are measured in fractions of seconds:

1/30th, 1/60th, 1/500th, 1/2000th

and even 1/4000th of a second are possible. Consider this: really slow speeds are 5 to 10

seconds, which passes by for us in a heartbeat.

Capturing Time

When you manually control shutter speed, you are telling your camera how much time you want your shutter to remain open.

Imagine that you're taking pictures of a train rolling past, and you want to make sure that the writing on the side of the cars is easy to read.

- At 1/1000th of a second, the writing is sharp and clear

- At

1/500th of a second the writing looks sharp, but you see minor blur when you magnify the image on your computer monitor

- At 1/80th of a second, NONE of the writing is legible: it all appears as a giant blur

This brings us to the key point:

The longer your shutter is open, the blurrier your photos become.

Let's take a look at 2 examples. This first image was taken at 1/60th of a second. Notice that both the subject and background look blurry.

This next image was captured at 1/1600th of a second. Now the subject is sharp. The background here appears blurry but it's not because of a slow shutter - it's because the in-focus area is limited to the subject. This in-focus zone is called the "depth of field".

So all you have to do to get sharp, clear images regardless of your subject is to ONLY use speeds of 1/1000th of a second or faster, right?

In theory, yes. In practice, there's a catch.

The Limits of Natural Light

The only thing standing between you and absurdly fast shutter speeds is Mother Nature.

Like a sponge, your sensor sucks up light. It needs to suck up enough light to form an image. Too little and all you get is black, too much and all you see is white.

1/2000th of a second doesn't provide your sensor with a lot of time to absorb light. Perhaps you see where I'm going with this.

The ONLY time that you can use shutter speeds in the 1/2000 to 1/4000 range is when there is a LOT of available light. In other words, it had better be a bright sunny day. Either that, or you're in the best-lit room of all time.

As the available natural light becomes brighter or darker, your maximum shutter speed adjusts accordingly:

- At sunrise, it might be 1/500

- From 11am to 2pm on a sunny day you can get 1/2000

- In the shade of a tree, it might drop to 1/250

- On an overcast day, it can be 1/100

- In the evening after the sun has set, you may only get 1/60

This relationship is key, because it helps you understand what you can and cannot do with shutter speed.

Put another way: if you're frustrated because you can't get clear shots of your child playing sports on a field at night with virtually no overhead light, now you know why.

It's not your fault, and it's certainly not the camera's fault. There's just not enough light to get the fast speeds that you desire.

So...What Else Can I Learn?

Join Our Community!

- Learn more about your digital SLR camera

- Get other opinions about camera models

- Share your photos and get feedback

- Learn new DSLR tips and tricks